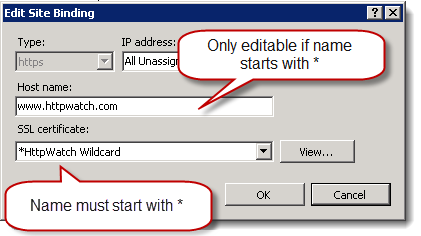

Myth #7 – HTTPS Never Caches

People often claim that HTTPS content is never cached by the browser; perhaps because that seems like a sensible idea in terms of security. In reality, HTTPS caching is controllable with response headers just like HTTP.

Eric Lawrence explains this succinctly in his IEInternals blog:

It comes as a surprise to many that by-default, all versions of Internet Explorer will cache HTTPS content so long as the caching headers allow it. If a resource is sent with a Cache-Control: max-age=600 directive, for instance, IE will cache the resource for ten minutes. The use of HTTPS alone has no impact on whether or not IE decides to cache a resource. (Non-IE browsers may have different default behavior for caching of HTTPS content, depending on which version you’re using, so I won’t be talking about them.)

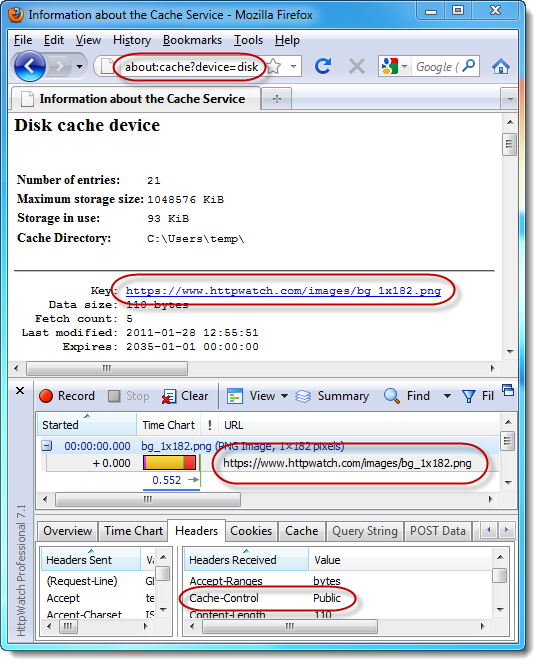

The slight caveat is that Firefox will only cache HTTPS resources in memory by default. If you want persistent caching to disk you’ll need to add the Cache-Control: Public response header.

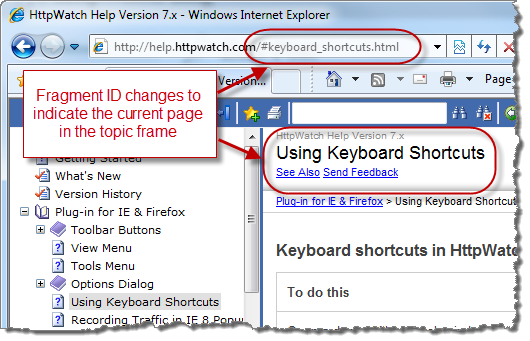

This screenshot shows the contents of the Firefox disk cache and the Cache-Control: Public response header in HttpWatch:

Myth #6 – SSL Certificates are Expensive

If you shop around you can find SSL certificates for about $ 10 a year or roughly the same cost as the registration of a .com domain for a year.

(UPDATE: you can get domain validated SSL certificates for free. See comment #1)

The cheapest certificates don’t have the level of company verification provided by the more expensive alternatives but they do work with nearly all mainstream browsers.

Myth #5 – Each HTTPS Site Needs its Own Public IP Address

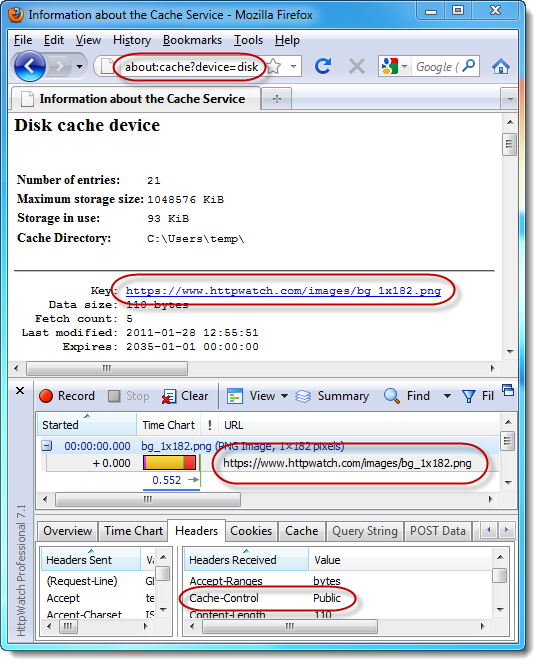

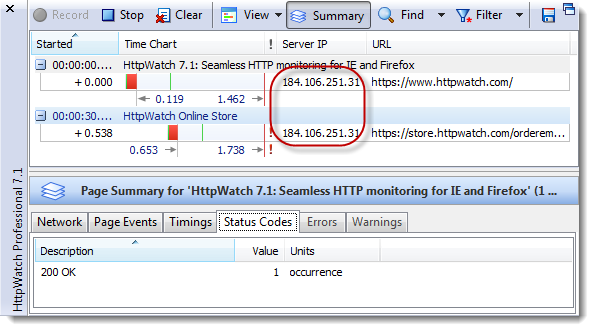

With the pool of IPv4 addresses running low this is a valid concern and it’s true that only one SSL certificate can be installed on single IP address. However, if you have a wildcard SSL certificate (from about $ 125 yr) you can have as many sub-domains as you like on a single IP address. For example, we run https://www.httpwatch.com, http://www.httpwatch.com and https://store.httpwatch.com on the same public IP address:

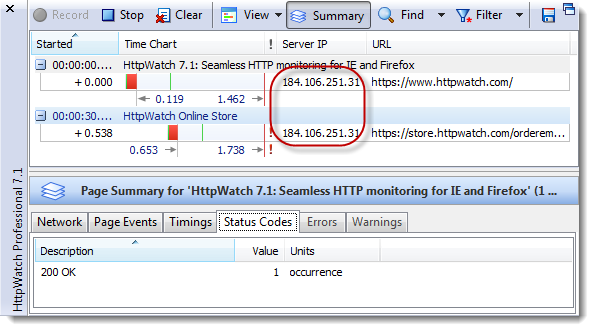

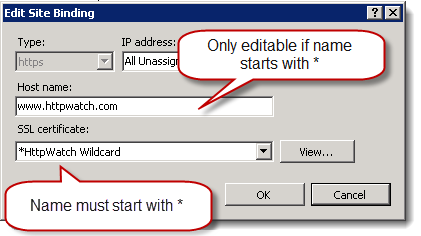

On IIS 7 there is a trick though to making this work. After adding a certificate you need to find it and rename it in the certificate manager so that the name starts with a *. If you don’t do this you cannot edit the hostname field for an HTTPS binding:

UPDATE: UCC (Unified Communications Certificate) supports multiple domains in a single SSL certificate and can be used where you need to secure several sites that are not all sub-domains.

UPDATE #2: SNI (Server Name Indication) allows multiple certificates for different domains to be hosted on the same IP address. On the server side it’s supported by Apache and Nginx, but not IIS. On the client it’s supported by IE 7+, Firefox 2.0+, Chrome 6+, Safari 2.1+ and Opera 8.0+. See comment #4 and comment #5.

UPDATE #3: IIS 8 now supports SNI

Myth #4 – New SSL Certificates Have to be Purchased When Moving Servers or Running Multiple Servers

Buying an SSL certificate involves:

- Creating a CSR (SSL Certificate Signing Request) on your web server

- Purchasing the SSL certificate using the CSR

- Installing the SSL certificate by completing the CSR process

These steps are designed to ensure that the certificate is safely transferred to the web server and prevents anyone from using the certificate if they intercept any emails or downloads containing the certificate in step 2).

The result is that you cannot just use the files from step 2) on another web server. If you want to do that you’ll need to export the certificate in other format.

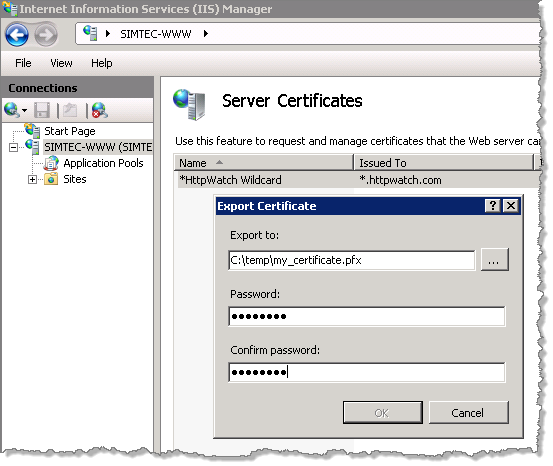

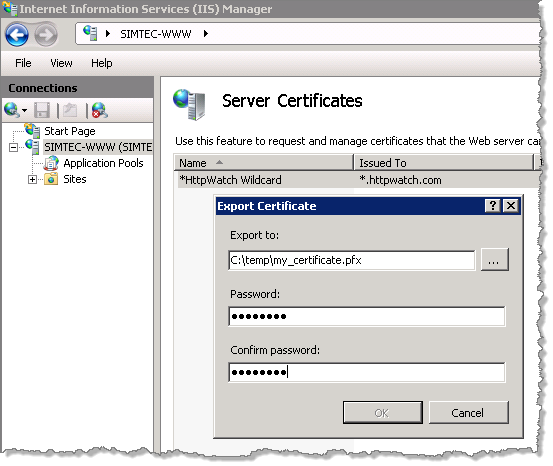

In IIS you can create a transferrable .pfx file that is protected by a password:

This file can be imported onto other web servers by supplying the password again.

Myth #3 – HTTPS is Too Slow

Using HTTPS isn’t going to make your site faster (actually it can – see below) but the overhead is mostly avoidable by following the tips in our HTTPS Performance Tuning blog post.

The amount of CPU resource required to encrypt the data can be reduced by compressing textual content and is usually not a significant on servers with modern CPUs.

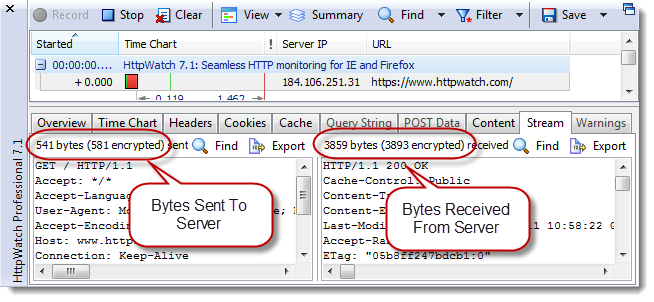

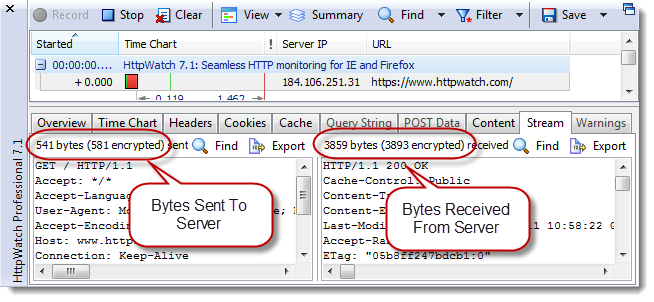

Extra TCP level round-trips are required to setup HTTPS connections and some additional bytes have to be sent and received. However, you can see in HttpWatch that this overhead is small once the HTTPS connection has been made:

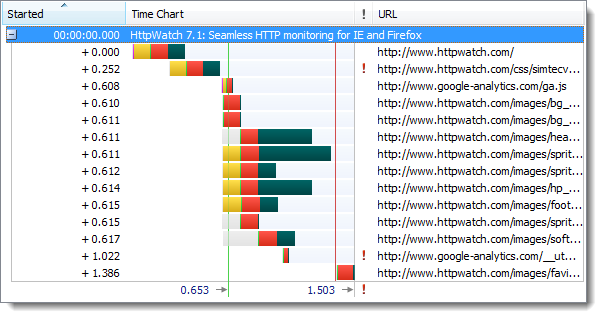

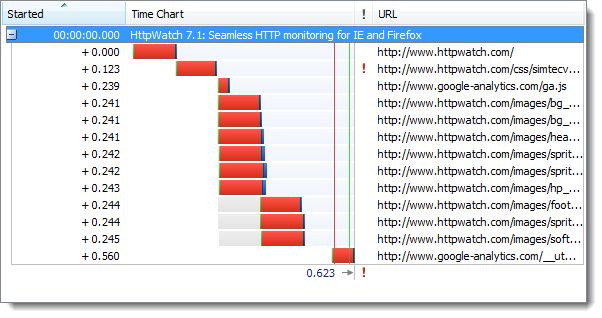

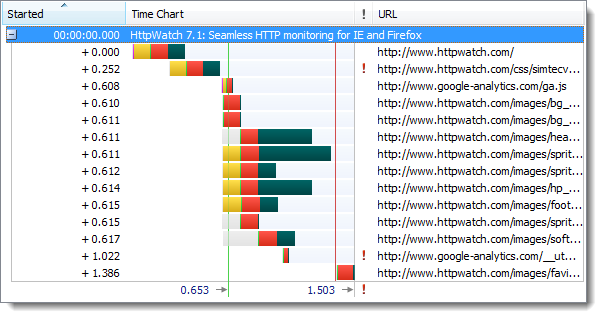

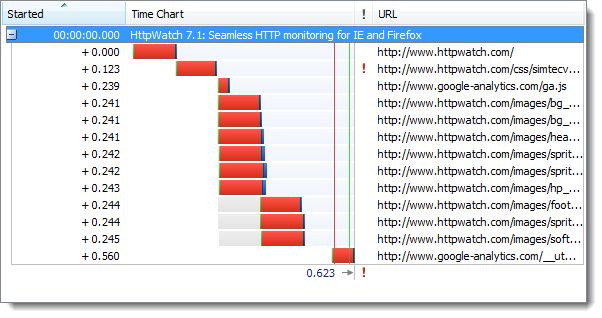

The initial visit to an HTTPS site is somewhat slower than HTTP due to the longer connection times required to setup SSL. Here’s a time chart of the page load for an HTTP site recorded in HttpWatch:

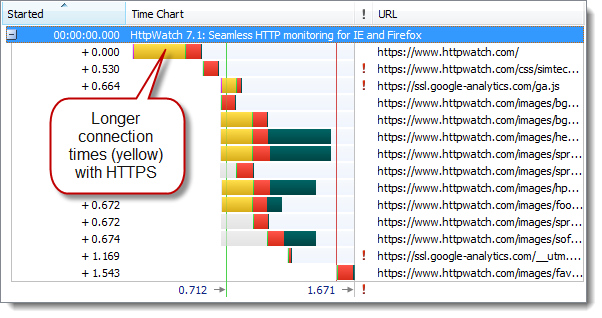

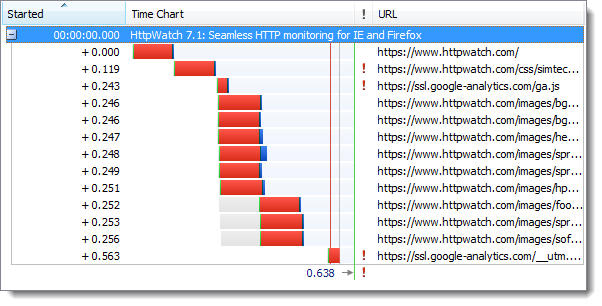

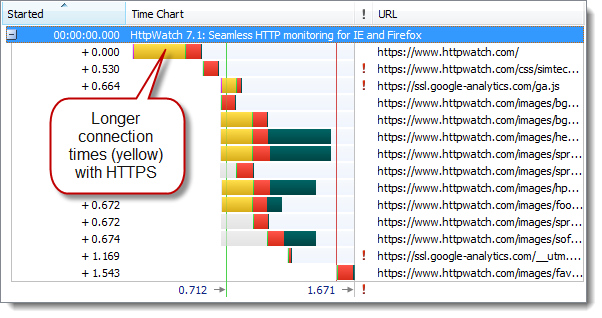

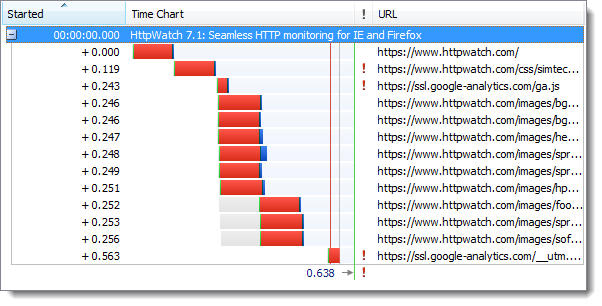

And here’s the same site accessed over HTTPS:

The longer connection times caused the initial page load to be about 10% slower. However, once the browser has active keep-alive HTTPS connections a subsequent refresh of the page shows very little difference between HTTP and HTTPS.

First, the page refresh with HTTP:

and then with HTTPS:

It’s possible that some users may even find that the HTTPS version of a web site is faster than HTTP. This can happen if they sit behind a coporate HTTP proxy that normal intercepts, examines and records web traffic. An HTTPS connection will often just be forwarded as a simple TCP connection through the proxy because HTTPS traffic cannot be intercepted. It’s this bypassing that can lead to improved performance.

UPDATE: A blog post by F5 challenges the claim the CPU overhead of SSL is no longer significant, but most of their arguments are refuted in this follow up.

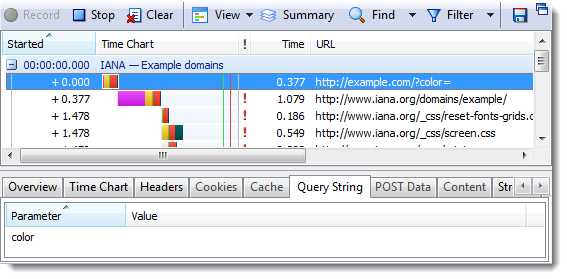

Myth #2 – Anything can go in Cookies and Query Strings with HTTPS

Although, a hacker cannot intercept a user’s HTTPS traffic on the network and read their cookie or query string values directly, you still need to ensure that their values can’t be easily predicted.

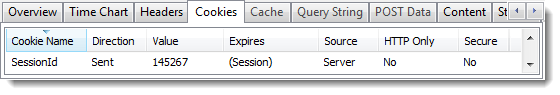

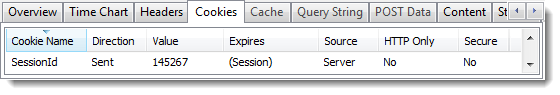

For example, one of the early UK banking sites used simple counter based numeric values for the session id:

A hacker could use a dummy account to see how this cookie worked and find a recent value. They could then try manipulating the cookie value in their own browser to hi-jack other sessions with nearby session id values.

Query string values are also protected on the network by HTTPS but they can still leak their values in other ways. For more details see How Secure Are Query Strings Over HTTPS .

Myth #1 – My Site Only Needs HTTPS for the Login Page

This is a commonly held view. The theory being that HTTPS will protect the user’s password during login but HTTPS is not needed after that.

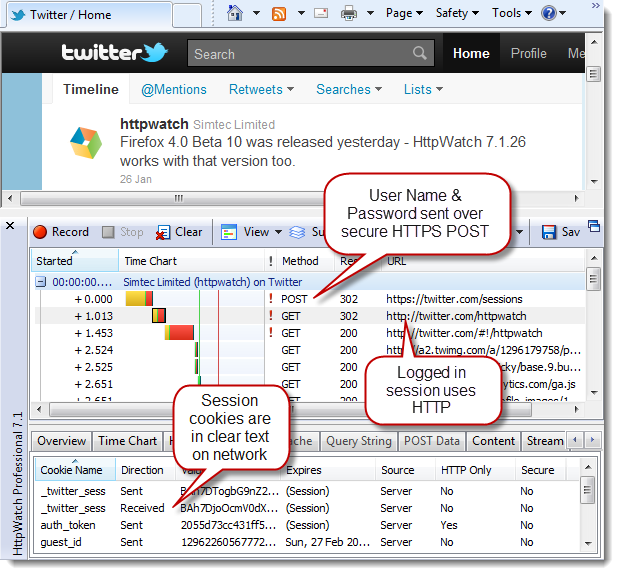

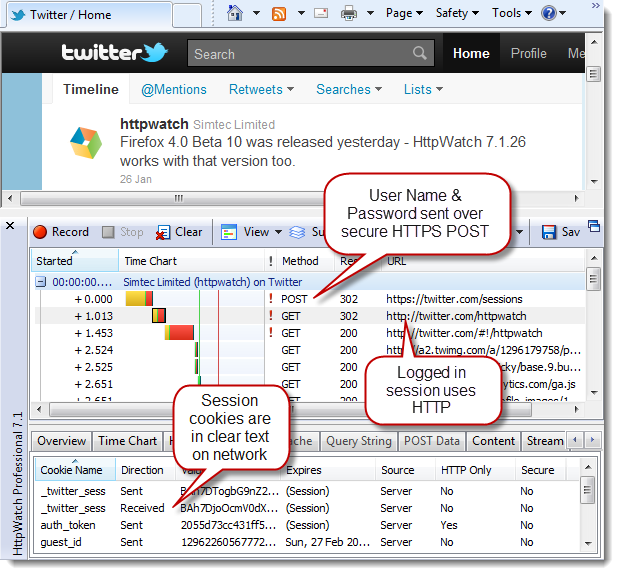

The recently released Firesheep add-on for Firefox demonstrated the fallacy of this approach and how easy it is to hi-jack someone’s else session on sites like Twitter and Facebook.

The free public WiFi in a coffee shop is an ideal environment for session hi-jacking because:

- The WiFi network doesn’t normally use encryption so it’s very easy to monitor all traffic

- The WiFi network probably uses NAT through a single IP address to access the internet. This means that a highjacked session appears to come from the same network address as the original login

There are lots of examples of this approach to security. For example, by default the Twitter signin page uses HTTPS but it then switches to HTTP after setting up the session level cookies:

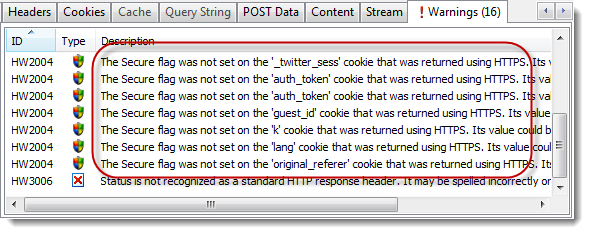

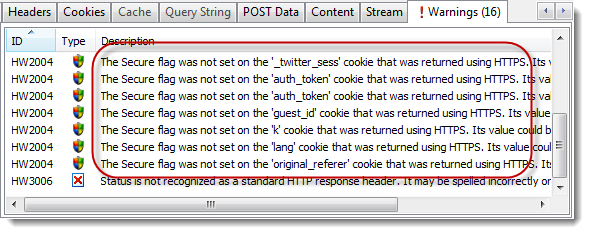

HttpWatch warns that these cookies were setup on HTTPS but the Secure flag wasn’t used to prevent them being used with HTTP:

Potentially someone in a coffee shop with Firesheep could intercept your twitter session cookies and then hi-jack your session to start tweeting on your behalf.

You can check SSL/TLS configuration our new SSL test tool

SSLRobot . It will also look for potential issues with the certificates, ciphers and protocols used by your site.

Try it now for free!

![]() March 11, 2011 in

Automation , HttpWatch

March 11, 2011 in

Automation , HttpWatch