In practice, you only need two settings to optimize caching:

- Don’t cache HTML

- Cache everything else forever

“Wooah…hang on!”, we hear you say. “Cache all my scripts and images forever?“

Yes, that’s right. You don’t need anything else in between. Caching indefinitely is fine as long as you don’t allow your HTML to be cached.

“But what about if I need to issue code patches to my JavaScript? I can’t allow browsers to hold on to all my images either. I often need to update those as well.”

Simple – just change the URL of the item in your HTML and it will bypass the existing entry in the cache.

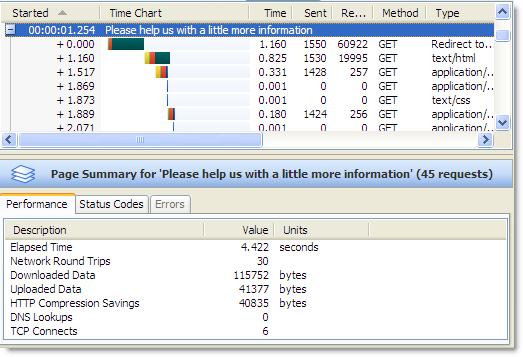

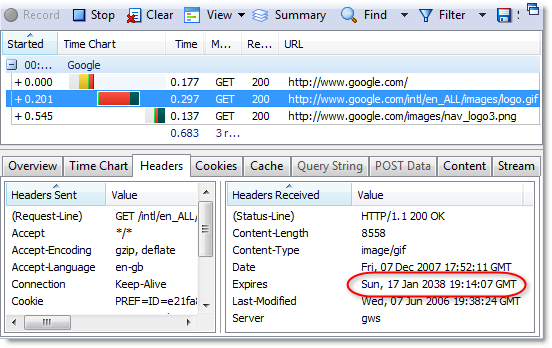

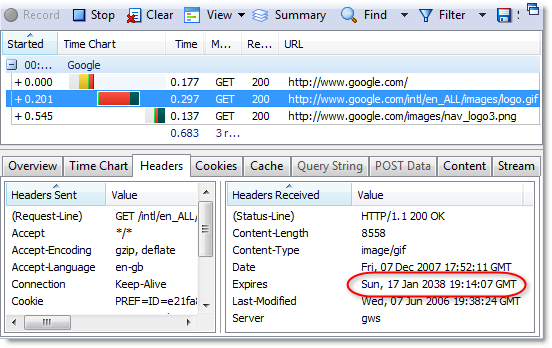

In practice, caching ‘forever’ typically means setting an Expires header value of Sun, 17-Jan-2038 19:14:07 GMT since that’s the maximum value supported by the 32 bit Unix time/date format. If you’re using IIS6 you’ll find that the UI won’t allow anything beyond 31-Dec-2035. The advantage of setting long expiry dates is that the content can be read from the local browser cache whenever the user revisits the web page or goes to another page that uses the same images, script or CSS files.

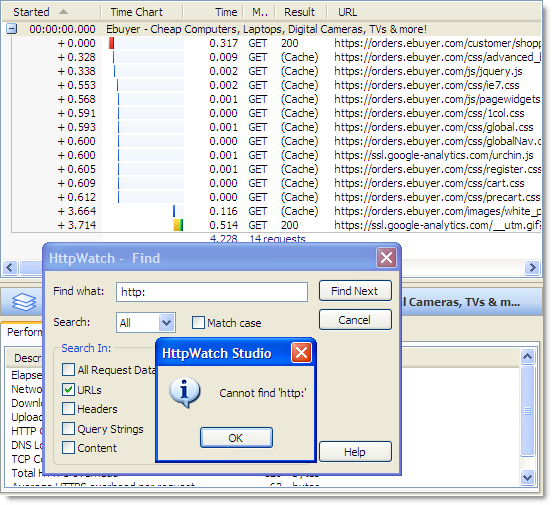

You’ll see long expiry dates like this if you look at a Google web page with HttpWatch. For example, here are the response headers used for the main Google logo on the home page:

If Google needs to change the logo for a special occasion like Halloween they just change the name of the file in the page’s HTML to something like halloween2007.gif.

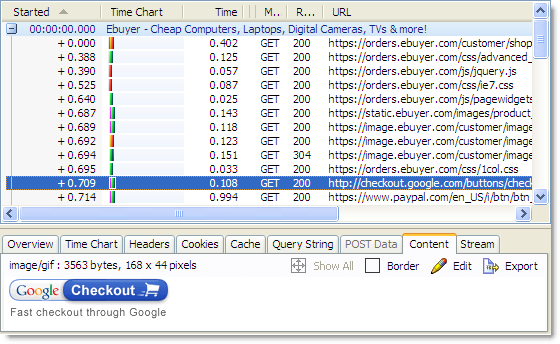

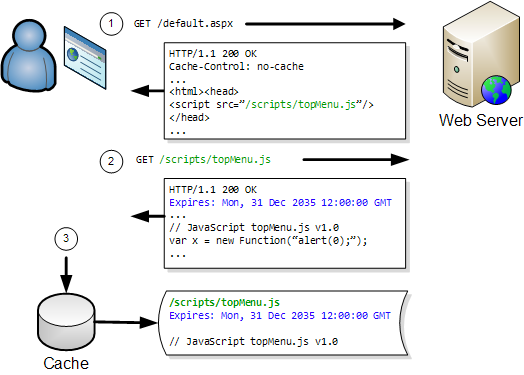

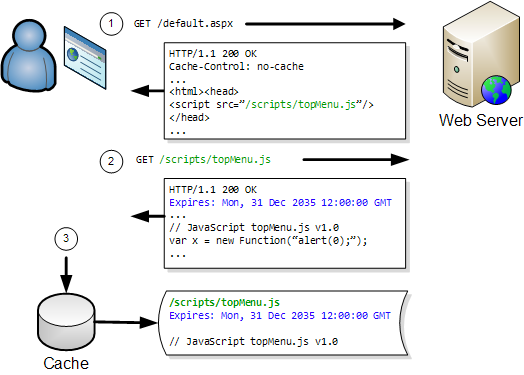

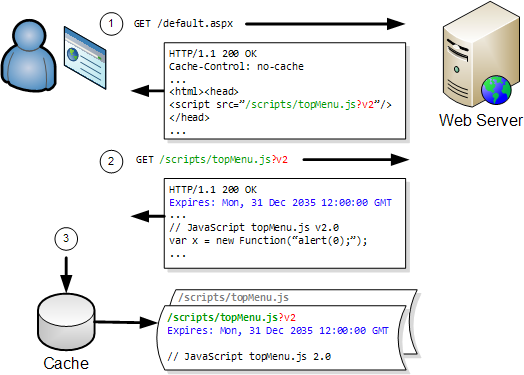

The diagram below shows how a JavaScript file is loaded into the browser cache on the first visit to a web page:

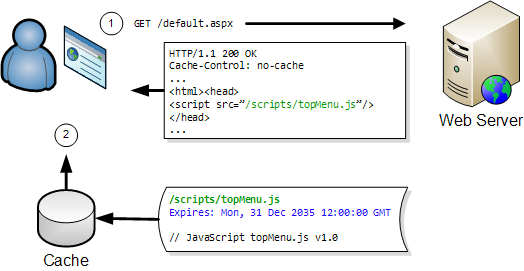

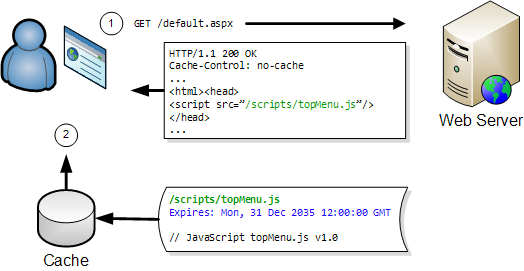

On any subsequent visits the browser only has to fetch the page’s HTML:

The JavaScript file can be read directly from the browser cache on the user’s hard disk. This avoids a network round trip and is typically 100 to 1000 times faster than downloading the file over a broadband connection.

The key to this caching scheme is to keep tight control over your HTML as it holds the references to everything else on your web site. One way to do this is to ensure that your pages have a Cache-Control: no-cache header. This will prevent any caching of the HTML and will ensure the browser requests the page’s HTML every time.

If you do this, you can update any content on the page just by changing the URL that refers to it in the HTML. The old version will still be in the browser’s cache, but the updated version will be downloaded because of the modified URL.

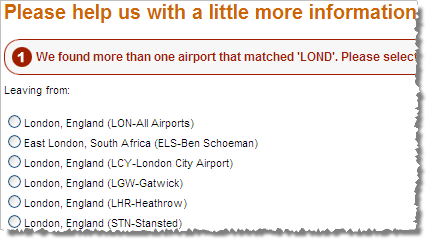

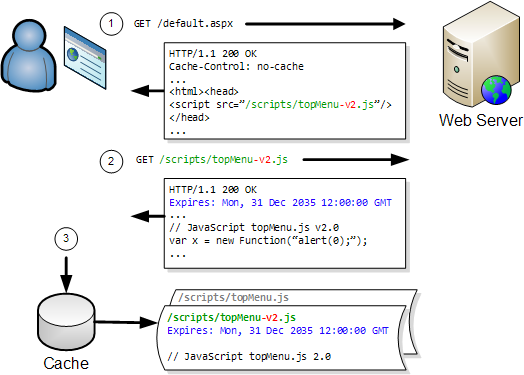

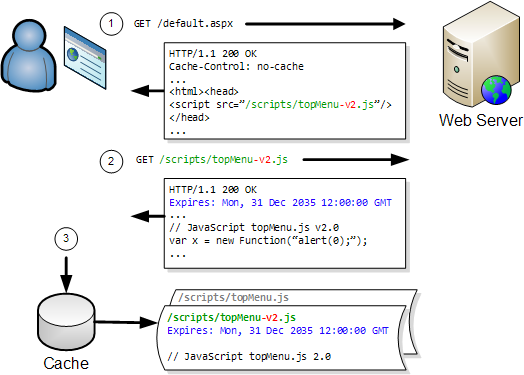

For instance, if you had a file called topMenu.js and you fixed some bugs in it, you might rename the file topMenu-v2.js to force it to be downloaded:

Now this is all very well, but whenever there’s a discussion of longer expiration times, the marketing people get very twitchy and concerned that they won’t be able to re-brand a site if stylesheets and images are cached for long periods of time.

In fact, choosing an expiration time of anything other than zero or infinite is inherently uncertain. The only way to know exactly when you can release a new version to all users simultaneously is to choose a specific time of day for your cache expiry; say midnight. It’s better to set indefinite caching on all your page-linked items so that you get the maximum amount of caching, and then force updates as required.

Now, by this point, you might have the marketing types on board but you’ll be losing the developers. The developers by now are seeing all the extra work involved in changing the filenames of all their CSS, javascript and images both in their source controlled projects and in their deployment scripts.

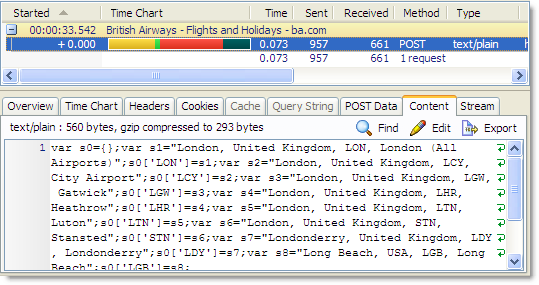

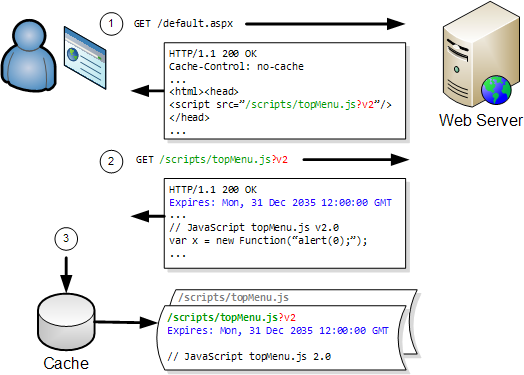

So here’s the icing on the cake; you don’t actually need to change the filename, just the URL. A simple way to do this is to append a query string parameter onto the end of the existing URL when the resource has changed.

Here’s the previous example that updated a JavaScript file. The difference this time is that it uses a query string parameter ‘v2’ to bypass the existing cache entry:

The web server will simply ignore the query string parameter unless you have chosen to do anything with it programmatically.

There’s one final optimization you can make. The Cache-Control: no-cache response header works well for dynamic pages as it ensures that pages will always be refreshed from the server; even when pressing the Back button. However, for HTML that changes less frequently it is better to use the Last-Modified header instead. This will avoid a complete download of the page’s HTML, if it has not changed since it was last cached by the browser.

The Last-Modified header is added automatically by IIS for static HTML files and can be added programmatically in dynamic pages (e.g. ASPX and PHP). When this header is present, the browser will revalidate the local, cached copy of an HTML page in each new browser session. If the page is unchanged the web server returns a 304 Not Modified response indicating the browser can use the cached version of the page.

So to summarize:

- Don’t cache HTML

- Use

Cache-Control: no-cache for dynamic HTML pages

- Use the

Last-Modified header with the current file time for static HTML

- Cache everything else forever

- For all other file types set an

Expires header to the maximum future date your web server will allow

- Modify URLs by appending a query string in your HTML to any page element you wish to ‘expire’ immediately.

![]() April 30, 2008 in

Caching , HTTP , HTTPS , HttpWatch , Internet Explorer

April 30, 2008 in

Caching , HTTP , HTTPS , HttpWatch , Internet Explorer