Four Tips for Setting up HTTP File Downloads

![]() March 24, 2010 in

Firefox , HTTP , HTTPS , HttpWatch , Internet Explorer , Javascript , Optimization

March 24, 2010 in

Firefox , HTTP , HTTPS , HttpWatch , Internet Explorer , Javascript , Optimization

Web sites don’t just contain pages; sometimes you need to provide files that users can download. Putting a file on your web server and linking to it from an HTML page is just the first step. You also need to be aware of the HTTP response headers that affect file downloads.

These four tips cover some of the issues you may run into:

Tip #1: Forcing a Download and Controlling the File Name

Providing a download link in the HTML is easy:

... <a href="http://download.httpwatch.com/httpwatch.exe">Download</a> ... |

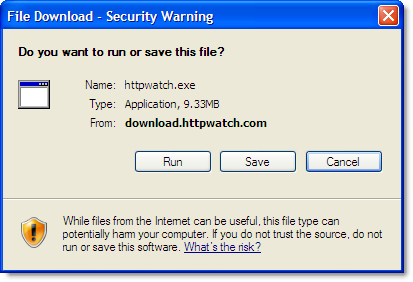

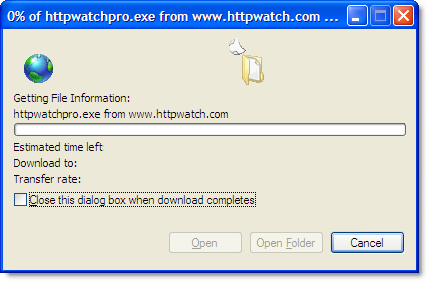

It works well for binary files like setup programs and ZIP archives that the browser doesn’t know how to display. A dialog is displayed allowing the user to save the file locally:

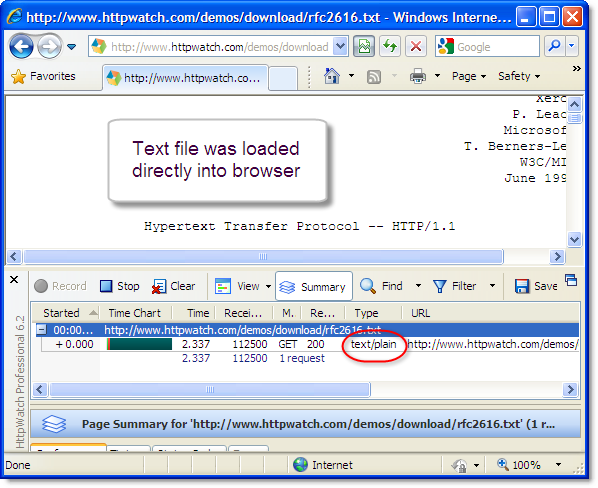

The trouble is that the browser behaves differently if the file is something that it can display itself. For example, if you link to a plain text file the browser just opens it and doesn’t prompt to save the download:

You can force the use of the file download dialog by adding the following response header:

Content-Disposition: attachment; filename=<file name.ext>

The header also allows you to control the default file name. This can be handy if you’re generating the content in something like getfile.aspx but you want to supply a more meaningful file name to the user.

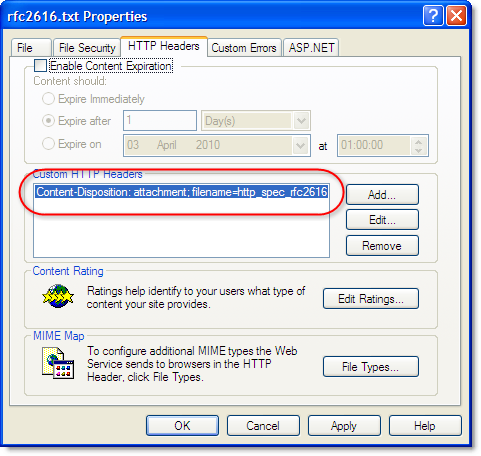

For static content you can manually configure the additional header in your web server. For example, here’s the setting in IIS:

For dynamically generated content you would need to add this header in the page’s server side code.

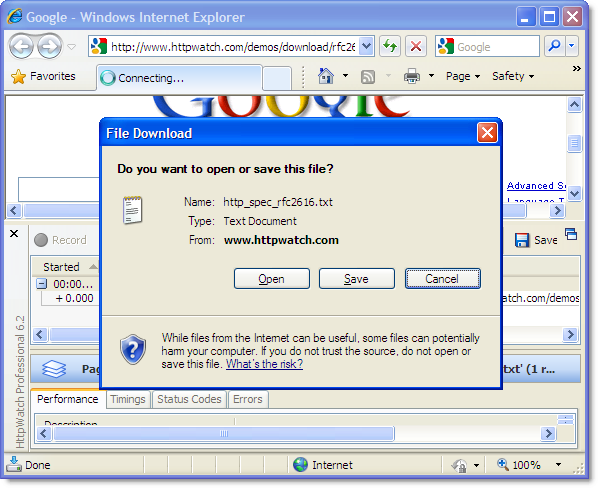

After adding the header, the browser will always prompt the user to download the file:

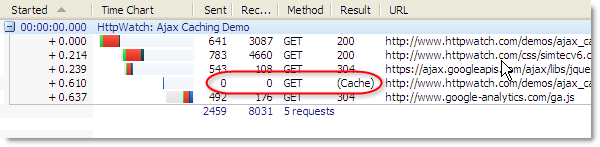

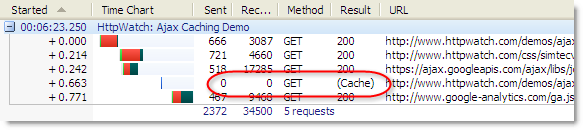

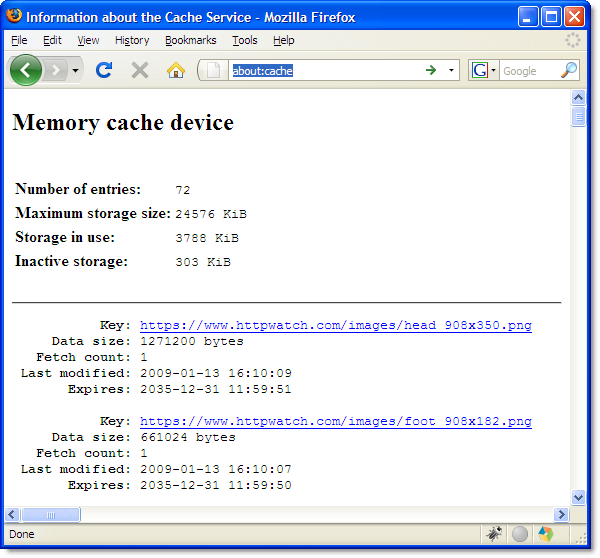

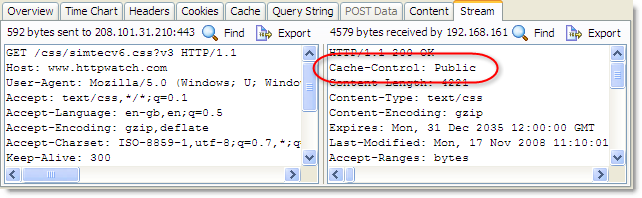

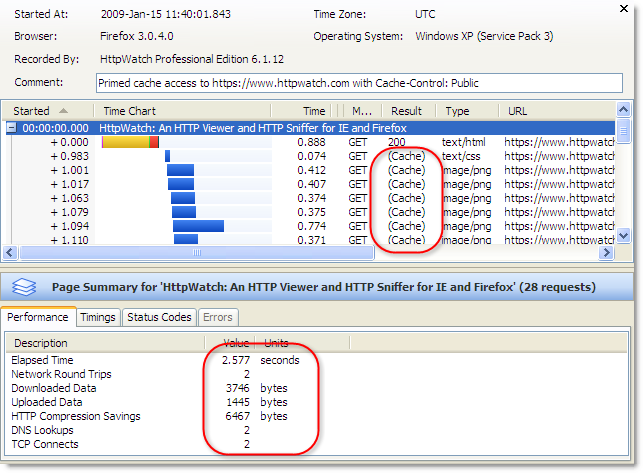

Tip #2: Use Effective HTTP Caching

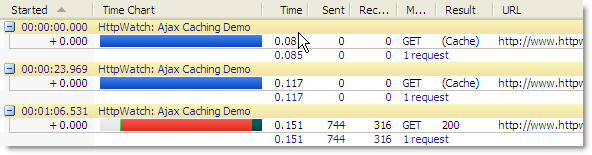

Like any other content, it’s worth setting up HTTP caching to maximize the speed of download and minimize your bandwidth costs. Usually content needs to expire immediately or be cached forever.

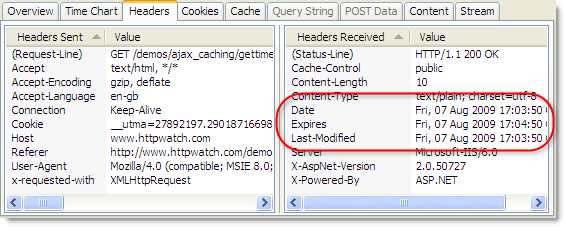

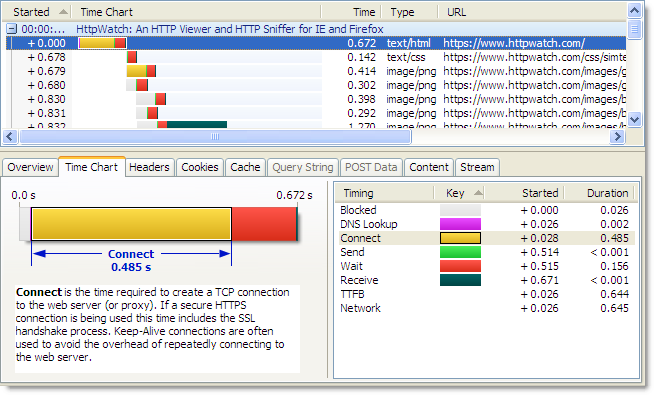

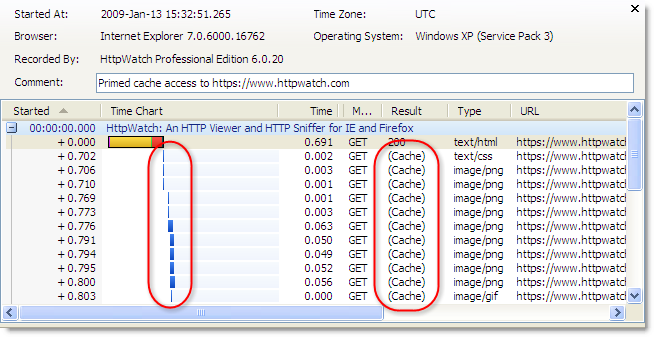

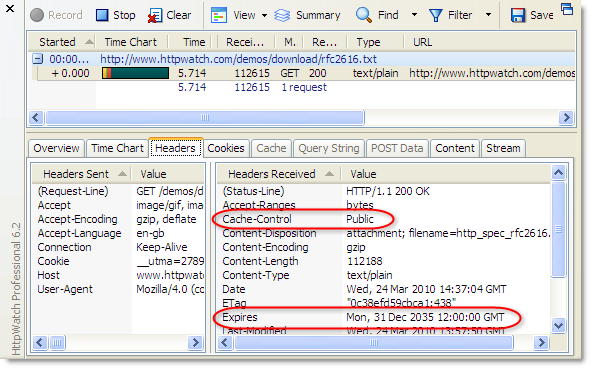

Our example download of the HTTP spec (RFC2616) could be cached forever because it is not expected to change. You can see here in HttpWatch we have set up a far futures Expires value and set Cache-Control to public :

This allows future downloads of the file to be delivered from the local browser cache or an intermediate proxy. If the file is subject to frequent changes, you may want to expire it immediately so that a fresh copy is always downloaded. You can do this by setting Expires to -1 or any date in the past.

Tip #3: Don’t break HTTPS downloads in IE

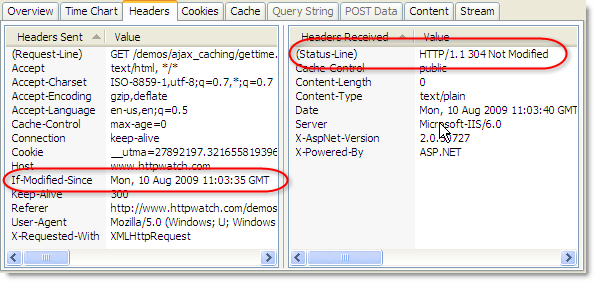

It’s tempting to use the no-store and no-cache directives with the Cache-Control response header to prevent any caching of a file that is often updated:

Cache-Control: no-store, no-cache

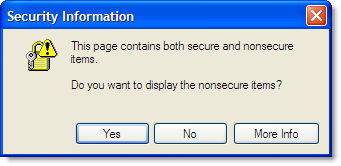

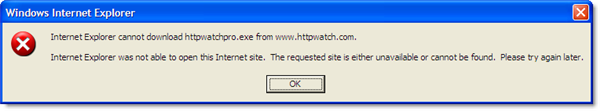

This works in Firefox, but watch out for Internet Explorer. It interprets these flags as meaning that the content should never be saved to the disk when HTTPS is being used and causes the file download dialog to hang at 0% for several minutes:

It eventually displays an error message:

There’s more information about this problem and other possible causes in a post on Eric Lawrence’s IEInternals blog.

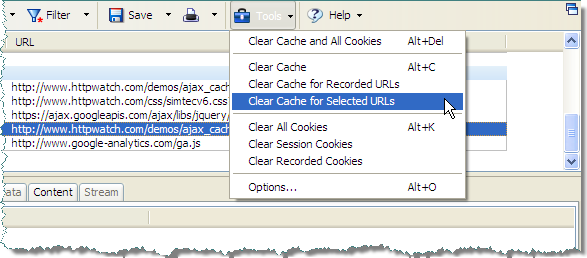

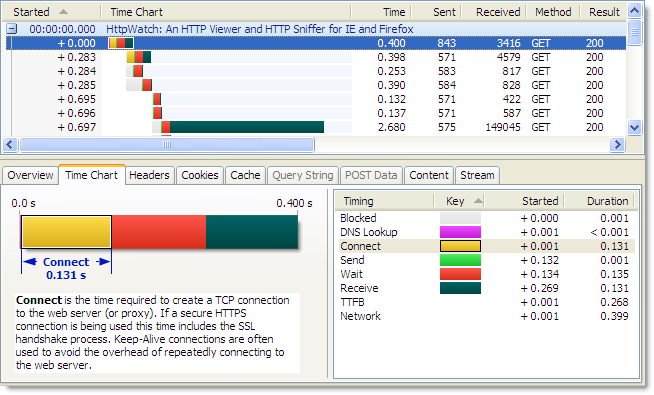

Tip #4: Don’t Forget to Setup Analytics

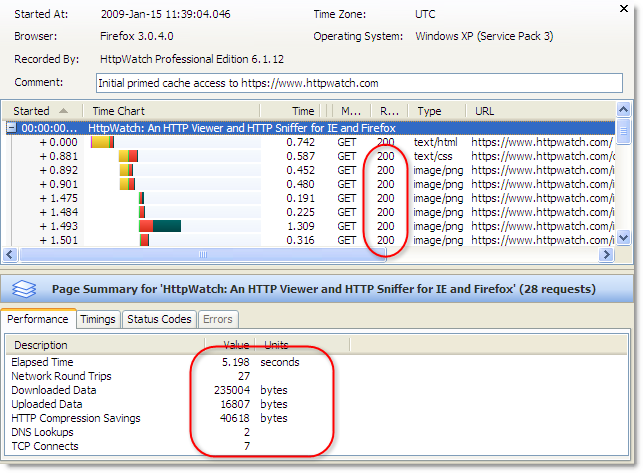

You’ll probably want to track file downloads along with other metrics from your web site. Javascript based solutions such as Google Analytics are very popular, but will not show file downloads by default. This is because downloading a file does not cause any Javascript to be executed.

With Google Analytics you need to add an onlick handler to enable download tracking:

... <a onclick="pageTracker._trackPageview('/httpwatch.exe');" href="...">Download</a> ... |

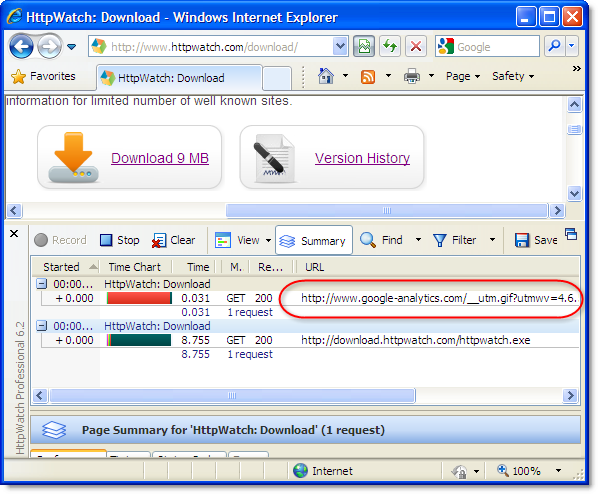

You can see the Google Analytics call being made just before the file download starts: